I talked on another blog post about some of the things people ate in prehistory, and I thought that I’d go into more detail about what people drank. Thanks to Merryn Dineley for her comments and additions on this blog post. Evidence for what people drank in prehistory comes from residue analysis of pottery vessels. Because they weren’t glazed, the pottery soaked up whatever it held, which can be identified in lab analysis.

Other evidence comes from experimental archaeology coupled with educated guesses based on what was available at certain times, both locally or by trade and our knowledge of the types of drinks available at later times and in other places in the world. Some pottery could have purposefully been sealed with animal fats, milk or beeswax, as demonstrated by the experiments done by Dana Millson, which complicates the picture somewhat (pers. comm. Merryn Dineley).

Fresh water flower from the Swallowhead Spring near Silbury Hill

Water, of course, is available from streams, rivers and springs. Usually settlements were placed close to fresh sources of water. Before the industrialisation of the world, water would have been pretty clean from these sources, though people could have boiled water too. Before people had pottery, water could be boiled in pits in the ground with hot stones dropped in, or in cooking skins over the fire. If necessary, snow could be melted the same way.

Boiling water in a wooden vessel to make stew

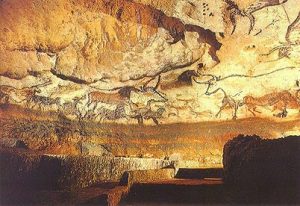

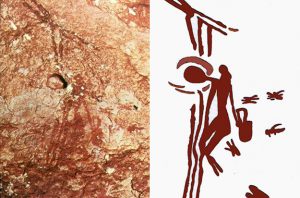

It is difficult to know whether hot drinks with any flavouring were drunk in prehistory. In the novels by Jean Auel about Palaeolithic Europe, the main character Ayla makes tea flavoured with different herbs each morning when she wakes up, but this is pure speculation. In a recent bushcraft magazine I received, a woman who had lived as a Palaeolithic person for several months in the wilderness of America made spruce needle tea and, instead of milk, used rendered buffalo fat. It sounds disgusting but it was apparently delicious!

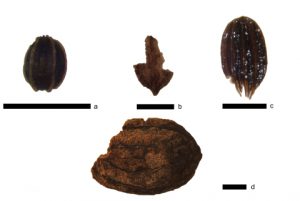

Milk would not have been available, past infancy, until the Neolithic when humans started to keep domesticated animals. Analysis of the absorbed fats in pottery sherds has identified that animals were milked extensively which is confirmed by the age and sex of the animal remains – dairy herds are mainly female (e.g. Copley et al 2005). Alongside the archaeological evidence of dairying, genetic evidence suggests that a mutation allowing ingestion of lactose post-infancy evolved and spread through the early farming population (Leonardi et al, 2012). The problem is, we can’t say for sure that people were drinking the milk directly because milk can be turned into so many other products like butter and cheese. It is also impossible to work out whether the milk was from cows, sheep or goats, although comparison with the animal bones can sometimes give a clue.

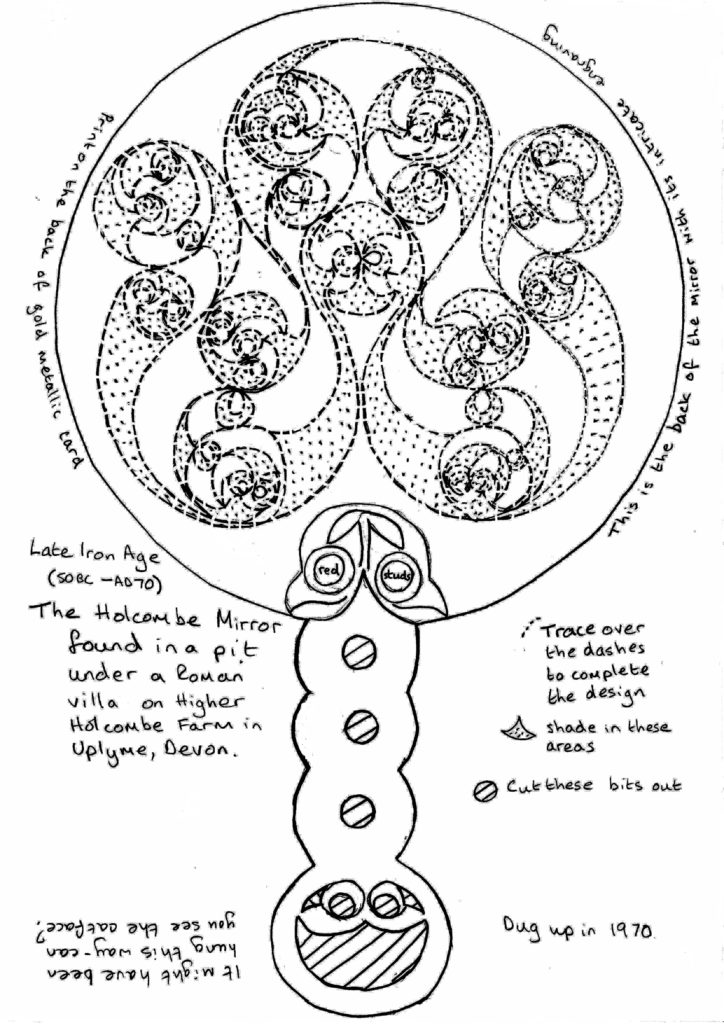

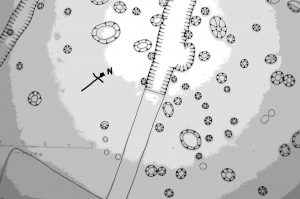

Could the floors of the Stonehenge Neolithic buildings, based on ones excavated at Durrington Walls, have been for malting and not living?

Coming into the Neolithic there might also have been another drink available. Something alcoholic. The work of several experimental archaeologists, e.g. Merryn Dineley, have demonstrated that ale could have been made using Neolithic technology. They had barley, pottery and fire, and early Neolithic buildings in the Near East often had well-kept floors which would be perfect for malting the barley. It is even possible that large Neolithic buildings in Britain were partially for malting grain (Dineley 2008, 2015, 2016).

Another alcoholic drink that would have been available would have been mead. This is made by fermenting honey in water, and it has been shown that bees were probably domesticated in the Neolithic (Guber 2017). Pollen grains identified in a pot from North Mains in Scotland and in coprolites (human poo) from the 3rd millennium BC (late Neolithic) contained meadowsweet pollen, a common flavouring and preservative for mead hence its name (Moe & Oeggl 2013). Meadowsweet has also been used in ale, though.

Me and my 5yo next to the Vix krater for scale

Wine was being made in the Mediterranean world from the fifth millennium BC, but didn’t get to Britain until much later, during the later Iron Age when it was imported in amphorae from the Roman Empire. The people who lived near what is now Chatillon-sur-Seine in France were importing wine from around 500 BC if not earlier. The huge Vix ‘krater’ was imported to hold and mix wine and water through the Greek trading port of Massalia, now Marseilles.

References

Copley et al, 2005. Dairying in antiquity. III. Evidence from absorbed lipid residues dating to the British Neolithic. Journal of Archaeological Science Volume 32, Issue 4, pp 523-546. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2004.08.006

Dineley, M 2008. The Durrington Maltsters. British Archaeology January/February 2008, pp30-31.

Dineley, M 2015. The craft of the maltster. Food and drink in archaeology 4. pp63-71.

Dineley, M 2016. Who were the first maltsters? The archaeological evidence for floor malting. Brewer and Distiller International 2016. pp34-36.

Guber, S 2017. Prehistoric Beekeeping in Central Europe – a Themed Guided Tour at Zeiteninsel, Germany. Exarc 2017/2. https://exarc.net/issue-2017-2/aoam/prehistoric-beekeeping-central-europe-themed-guided-tour-zeiteninsel-germany

Leonardi, M, Gerbault, P, Thomas, M.G, & Burger, J, 2012. The evolution of lactase persistence in Europe. A synthesis of archaeological and genetic evidence. International Dairy Journal 22, pp88-97.

Moe, D & Oeggl, K 2014. Palynological evidence of mead: a prehistoric drink dating back to the 3rd millennium b.c. Vegetation history and archaeobotany, Volume 23, Issue 5, pp 515–526. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00334-013-0419-x

![Gundestrup Cauldron. By Rosemania (http://www.flickr.com/photos/rosemania/4121249312) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/800px-Silver_cauldron-300x196.jpg)

![Basse-Yutz flagons. By British_Museum_Basse_Yutz_flagons.jpg: [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/British_Museum_Basse_Yutz_flagons_1-300x185.jpg)

![St Chad's Gospel. By The original uploader was Claveyrolas Michel at French Wikipedia (Transferred from fr.wikipedia to Commons.) [CC SA 1.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/sa/1.0/)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Lichfield_monog_Christ-227x300.jpg)

Salisbury Museum runs two workshops on prehistory. One is focused on the

Salisbury Museum runs two workshops on prehistory. One is focused on the

![18th century engraving of a Wicker Man. By UnknownMidnightblueowl at en.wikipedia [Public domain], from Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/WickerManIllustration-214x300.jpg)

![Edinburgh Beltane Festival 2012. By Stefan Schäfer, Lich (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/640px-Edinburgh_Beltane_Fire_Festival_2012_-_Bonfire-300x200.jpg)