Derbyshire, being mostly upland, has got some great surviving prehistoric archaeology. It is well furnished with megalithic monuments from the Neolithic and early Bronze Age and some later Bronze Age and Iron Age hillforts, as well as later industrial history.

Here are some of the main sites in chronological order:

-

Engraved horse head on rib bone from Creswell Crags. By Dave from Nottingham, England – The Ochre Horse – 12500 Years Old!, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=12366019

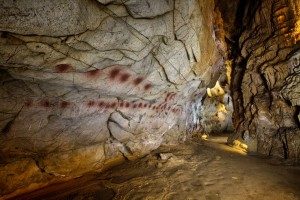

At the border with Nottinghamshire is Creswell Crags, which have Britain’s best-preserved Palaeolithic cave art. This art is engraved rather than painted, and there are remains of both Neanderthal and Homo sapiens occupation. It is thought that hunters came to the area close to the edge of the ice sheet, possibly to hunt horses, around 14,000 years ago. Someone dropped an animal rib bone engraved with the head of a wild horse. There is a great visitor centre there, tours of the caves and a museum. There is more on the cave art on Teaching History with 100 Objects website.

-

Arbor Low. By Michael Allen, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3869992

There are several stone circles and isolated standing stones in Derbyshire, and many are accessible. Arbor Low, near Youlgreave, is one of the most famous. It is known as a recumbent stone circle as the stones are lying down, having possibly been toppled at some point in its history. The stones were an early Bronze Age addition to a henge monument alongside a round barrow (a burial mound), which is a space encircled by a bank and ditch and dating to the later Neolithic. Nearby is an earlier Neolithic oval barrow with a superimposed early Bronze Age round barrow at Gib Hill, and a possible avenue of earth between the two. The local landowner charges £1 to cross the land to the henge and stone circle.

- The Bull Ring is another later Neolithic henge, in Dove Holes. It doesn’t have any standing stones associated with it, though there are rumours that there used to be in the 18th century. Like Arbor Low it is also associated with an oval barrow nearby.

- There are also the Nine Ladies on Stanton Moor. This is an early Bronze Age circle of nine stones said to have been petrified ladies, cursed for dancing on a Sunday. There are other standing stones and cairns (burial mounds made of heaped stones) on the moor, including the King Stone, visible from the Nine Ladies. The stones are very small, under a metre in height.

- Hob Hurst’s House is a possible early Bronze Age square burial mound near Beeley. Like many of the burials of a similar date in Derybshire, it was excavated in the 19th century and is said to have contained a stone cist (a little chamber) for some burned bones. Hob Hurst is the name of a local mythical goblin. These last two are free to visit.

-

Rock art on Gardom’s Edge. By Roger Temple, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13089144

Gardom’s Edge is a rocky outcrop near Baslow that contains standing stones, rock art of cups and rings, and hut circles from the late Neolithic or early Bronze Age.

- Robin Hood’s Stride near Elton is a natural tor, but there are remains of house platforms, probably dating to the early Bronze Age, there as well.

- Carl Wark on Hathersage Moor is a hillfort, and these are often Iron Age in date, but there hasn’t been any excavation there so it is possible it may, like other hillforts in the region, be later Bronze Age in date. It has a rampart faced with stone, which is unusual.

- Mam Tor is another hillfort, near Castleton, and has seen some excavation. It dates to the later Bronze Age, starting as a palisaded settlement with later earthen ramparts. There are also two earlier Bronze Age round barrows on the summit, from an earlier use of the hill as a burial place. There is a possible trackway that leads south from the hill past two other hillforts. Be careful up there as the sides of the hill have landslides as they are made of shale, and when I first visited I had to shelter in the rampart ditch from a white-out!

This is just a selection of the huge amount of prehistoric archaeology to be found in Derbyshire. There are many more instances of rock art, standing stones, burial mounds and hillforts to be found.

Museums and other places to visit include:

- Derby Museum and Art Gallery has lots of stone tools, including some from Creswell Crags and other prehistoric monuments mentioned above, plus a Bronze Age logboat dated to about 1400 BC from the Hanson gravel pit at Shardlow. It was preserved by waterlogging and contained a cargo of sandstone.

- Buxton Museum and Art Gallery has archaeological collections including Mesolithic microliths from Kinder Scout and Edale, Neolithic finds from Arbor Low and Stanton Moor and some Pleistocene (Ice Age) animal remains from Dove Holes such as sabre-toothed cat, mastodon and hyena.

- Creswell Crags museum has already been mentioned above. This focuses on Ice Age material as well.

- A lot of archaeological material from Derbyshire is in Weston Park Museum in Sheffield.