Hi, this is Kim Biddulph here, Schools Prehistory Director. It has been my life’s goal to prove to children and adults alike who visit museums, historic houses and archaeological sites that I have worked at that people in the past were not stupid. I consider it a triumph if someone I have talked with has the spark of revelation that people in the past were just like us.

Me teaching a shadow puppet session when I worked at the Pitt Rivers Museum, drawing done by the head of education there, Andrew McLellan

I am helping the Pitt Rivers Museum develop a Stone Age workshop at the moment and I count it particularly important to ensure that the philosophical approach to people in prehistory is the same as that museum’s approach towards the makers of many of the objects in the collections from around the world. It is both an archaeological and anthropological museum. Instead of grouping its anthropology collection into cultures the museum is famous for arranging its collections by type. The original impetus for this was General Pitt Rivers interest in the evolution of the sophistication of objects from ‘primitive’ societies to more ‘civilised’ societies. The museum now keeps the same arrangement but for a fundamentally different reason. The philosophy of the museum is to reject the idea that societies evolve from primitive to civilised and to emphasise the ingenuity of humankind across the globe to solve problems with the materials and technology they have to hand. We all face the same problems, how to house ourselves, feed ourselves, travel, keep warm with clothes and fires, play, adorn our bodies to look important or beautiful, but we all do it slightly differently.

I am concerned that the idea that prehistoric European societies were primitive and have evolved to our civilised state is being taught to children in our schools now. I have heard a teacher say that people invented farming once they learned how to use their brains. I have been told of an occasion when a museum workshop leader said that people invented metal-working once they became cleverer and found an alternative to mere stone. If we say that prehistoric people were stupider than us, it logically follows that we are also saying that our own contemporary societies with similar technology to our prehistoric ancestors are actually stupider than us.

Let’s approach prehistoric periods with more subtlety and appreciation of their ingenuity. Lets remember that inventions were probably realised following accidents or developed out of small scale changes in behaviour spurred by changing cultural practices. Farming was invented in the Near East and spread (as an idea) across Europe slowly, taking over 6000 years to reach Britain in 4000 BC. The invention of pottery vessels alongside farming was spurred on by the increasingly sedentary lives of farmers in the Near East and someone accidentally dropping clay into a fire, probably. The better control of fire to make better fired pots probably led to the discovery of metal, when a piece of copper ore was dropped into a fire. Imagine a similar scenario for iron, which has an even higher smelting temperature.

The people who took advantage of these new inventions and technologies were not stupid, in fact they were very intelligent, seeing the opportunities that these technologies gave them not only for easier access to food and better tools, but initially probably because the knowledge and practice of this technology gave them an opportunity to get one over on their neighbours.

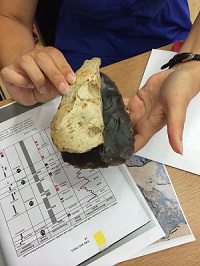

Early copper and bronze tools were not better than flint. Until bronze-smiths learned how to make better bronze tools, flint was still sharper and stronger than bronze. Early iron was also not better than bronze straight away. Smiths now had to learn to add carbon to the cutting edge to make it stronger and less brittle in order for iron to displace bronze.

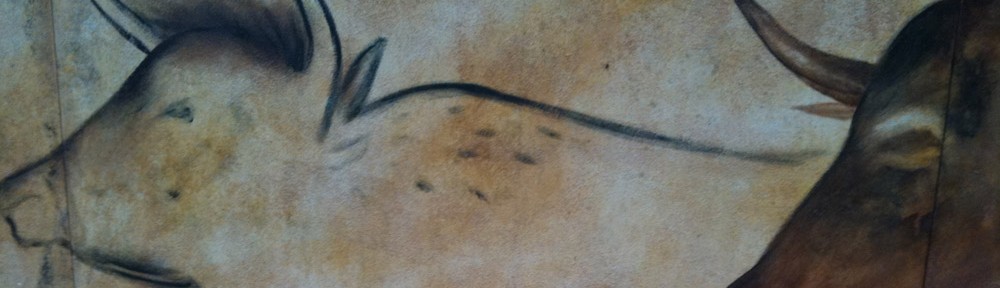

You only have to see photos of the amazing paintings at Chauvet Cave in France to know that the earliest anatomically modern humans in Europe were not stupid. But what to say about Neanderthals or other early species of human e.g. Homo heidelbergensis or Homo erectus? How do we talk about the mental capacity of different species of humans? I think, given that they were the ones who first controlled fire, who created beautifully flaked symmetrical handaxes, and may have been experimenting with art hundreds of thousands of years before Chauvet, that we shouldn’t underestimate them either.

———————————————————————————————————————————–

*UPDATE*

We visited the National Association for Primary Education‘s conference last Friday on 24th April 2015. We found a kindred spirit in a teacher who wanted to show his kids that people in the Stone Age were not stupid. You can imagine how we cried for joy! He recommended a video that showed how cave paintings were not just static portraits of animals but were painted in such a way that they were like animations, and would have moved in the flickering firelight. We didn’t have time to get details but the hive mind of Twitter, specifically Helen Hall @JellyheadNelly, found it for us. It was the work of archaeologist Marc Azema, and here it is.

![Is this what the Blackweater Valley looked like 30,000 years ago? Neanderthals and mammoths together. By Randii Oliver [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](http://schoolsprehistory.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/640px-neanderthals_-_artists_rendition_of_earth_approximately_60000_years_ago.jpg)

![Colin Smith [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://schoolsprehistory.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/st_anns_hill_-_geograph-org-uk_-_1165406.jpg)

![Three Thornborough Henges seen from the air. By Tony Newbould [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://schoolsprehistory.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/thornborough_henge.jpg)

![Model of Mesolithic house at Mount Sandel, Northern Ireland. By Notafly (Own work) [CC-BY-SA-3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://www.schoolsprehistory.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/320px-ulstermuseumprehistoryme1.jpg?w=300)

![Three Thornborough Henges seen from the air. By Tony Newbould [CC-BY-SA-2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](http://schoolsprehistory.files.wordpress.com/2014/05/thornborough_henge.jpg?w=300)